According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, as of 2019, of the more than 1.7 million professionals working in engineering occupations in the United States, only about 16,000 were Black women. That represents less than 1% of the engineering workforce.

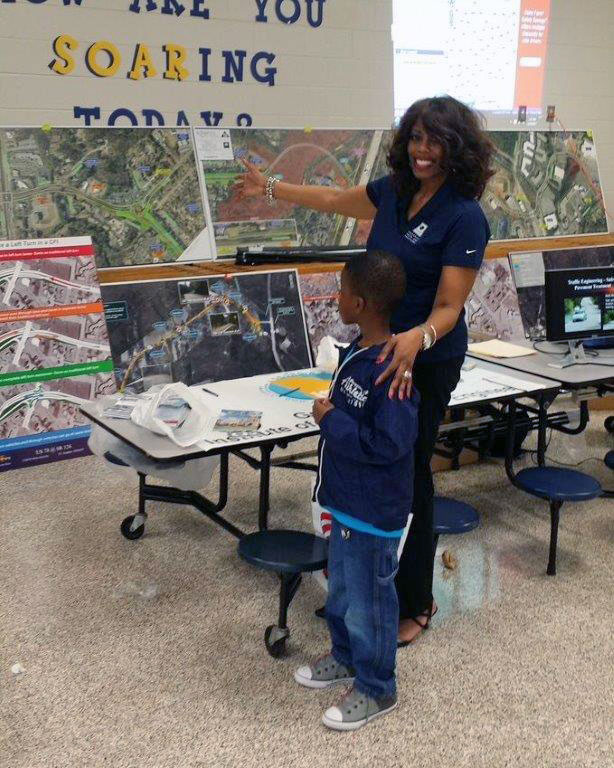

We recently sat down with Carla Holmes, a senior transportation engineer in Gresham Smith’s Alpharetta office and an at-large member of the firm’s DE&I (Diversity, Equity & Inclusion) Advisory Committee, to discuss her thoughts on why minorities are underrepresented in the engineering industry. We also learned a little more about her personal career journey in the process.

How did you get interested in becoming an engineer?

Carla Holmes: I actually wanted to be a writer when I was in high school, which was back in the 80s. But I was also strong in math and science and eventually began to show an interest in engineering. Between my junior and senior years, I ended up enrolling in an engineering program at Tuskegee University, even though engineering wasn’t initially on my radar since there were very few women or women of color in that industry.

From there, I went to Georgia Tech where I graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering in 1988 and began working for the Georgia Department of Transportation. I was proud to experience many “firsts” at GDOT—from being the first Black female Assistant Area Engineer to being the first Black female State Traffic Operations Engineer.

You were also the first Black female president of the Georgia Section of the Institute of Transportation Engineers, Inc., and the first Black female to hold offices and board positions in some of the other professional societies in which you’re a member. How did it feel to break down those barriers, and what were some of the challenges associated with those “firsts?”

Carla: People can say: Oh, I don’t notice color. But when you’re a Black female in the engineering industry, it’s probably the first thing people notice about you. It’s inevitable that it’s going to be a “thing” when you’re a minority of such a degree in this kind of field.

While it was very rewarding to get the opportunity to do things that no one who looked like me had ever done before, those “firsts” came with a tremendous amount of pressure. I remember thinking to myself: Hey, this is the first time they’ve placed a Black female in this role, so you better not screw up or it might impact another minority coming in after you.

I don’t recommend putting that additional pressure on yourself, but it inspired me to work even harder and to go the extra mile. I got my Master of Science in Civil Engineering in 1999 and continued to seek out that kind of credibility throughout my career through education, licensures and certifications, as well as active involvement in professional societies. I never want to give anyone cause to say: She doesn’t deserve that position, but rather that she’s earned it.

“I remember thinking to myself: Hey, this is the first time they’ve placed a Black female in this role, so you better not screw up or it might impact another minority coming in after you.”

Do you feel that you have been overlooked for positions or not given certain opportunities because you’re a woman of color?

Carla: I’ve only had one instance when a client expressed they didn’t want me to be PM on their project. I felt that was a racial thing, especially because they didn’t know anything about my work before coming to that decision. I don’t believe I’ve been overlooked for a position because I’m a Black female, although I know it does happen. I’ve been very fortunate to have had some amazing mentors throughout my career, both at GDOT and at Gresham Smith—people who have given me opportunities that others may not have.

You’ve been a practicing engineer for 32 years. What advice do you have for other women of color who are thinking about going into the profession?

Carla: I’d tell them that it might not always be easy, but don’t feel that just because you’re a Black female you’re going to be excluded from things because it’s not automatically the case. In my career, I’ve seen that doors don’t necessarily close in your face because of your race or your gender. There are people out there who will give you opportunities, regardless of color, race or gender, based on the merits of your work.

I do believe, however, that Black females have to bring a lot more to the table to be seen as deserving to be at the table. So, I recommend that women of color take advantage of as many professional and leadership development opportunities as they can so they are ready to “show up and show out” when they get there.

How will you continue to help other minorities who are considering a career in the engineering profession?

Carla: In my own career, I’ve arguably been equal parts role model and a cautionary tale. My hope going forward is to play some small part in making engineering more attractive to minority students and more rewarding for our young professionals. I want to help alleviate the stresses that come from feelings of not belonging and from the isolation that can come from being a first or an only.

I want to be part of a support system that acknowledges the dissimilar experiences minorities in engineering may have from their majority counterparts and to help them find pathways through—or around—those experiences to a long and successful career.

How can A/E firms transform their policies and practices to recruit more women and minorities in both architecture and engineering?

Carla: Human nature tends to give us an affinity for people who either are like us or who conform to the status quo of our environment. I would say that A/E firms should acknowledge that and challenge it in their recruiting policies and practices. In white, male-dominated fields such as engineering, unconscious bias may lead to looking more favorably at those candidates.

Gender, race, ethnicity and life experiences that are shaped by those things make us different. It is vital that recruiters and those making hiring and promotion decisions look beyond those differences to give all qualified candidates a chance. Encourage them to step outside their comfort zone and look further than what may be the “typical” engineer or architect. Inclusivity doesn’t mean taking away from the majority—it means making the entire organization better.