As healthcare designers, we love to talk and dream about sustainable “hospitals of the future”. Talk is cheap, however, and such conversations mean little if we cannot balance those eco-friendly dreams with the fiscal stresses our clients face and prove the return-on-investment (ROI) of the strategies that we so enthusiastically discuss.

To maximize ROI, sustainability strategies should carefully balance fiscal, sociological and ecological interests- the triple bottom line. From an operational standpoint, it is fairly easy to prove the fiscal benefits of sustainable strategies, particularly those that reduce energy consumption. A study cited in Healthcare Design, for example, projects $980 million in savings if certain sustainable strategies were implemented at all U.S. hospitals. It is important to remember, however, that a hospital’s operational budget is often entirely separate from its capital or new construction budget. Strategies that lower operational costs can still be cost-prohibitive from a capital standpoint. This is especially true for design features that focus primarily on social or ecological benefits, which can have higher up-front costs and longer payback periods. Our challenge, then, is twofold: proving the ROI of sustainable strategies and, where possible, improving ROI by minimizing first costs. It is not an easy task, certainly, but it is arguably one of the most important we face.

Look for low-hanging fruit

Some sustainable design strategies can be achieved at little to no cost. For example, in Kaiser Permanente’s “Small Hospital, Big Idea” design competition, our team modified the building’s orientation to minimize east-west facades in favor of north-south facades. Made early in the design process, that adjustment had little impact on overall square footage cost and changes in sun angles generated projected savings of $2 million over a 20-year period. Such adjustments, if not blockbusters in and of themselves, can be important building blocks in an overall sustainability plan.

Look for ways to subsidize higher costs

The reality is that many high-impact sustainable features are accompanied by significant up-front costs. Given that reality, designers should look for ways to mitigate initial costs. Also in the Kaiser contest, Gresham Smith’s team demonstrated that photovoltaic cells could produce 75 percent of the power needed to operate the hospital. With the other 25 percent of power needed produced by on-site wind turbines, the proposed building was a net-zero energy hospital. The photovoltaic cells initially appeared to be cost-prohibitive, with high first costs and a lengthy 15-year payback. However, designers proposed a partnership with local utility companies, allowing those companies to partially own the photovoltaic cells and subsidize costs to the hospital. Though this model, in the case of the competition, was hypothetical, utility companies expressed significant interest and Kaiser has successfully formed similar partnerships on a smaller scale. The strategy certainly warrants further exploration, and is a great example of balancing fiscal and ecological interests.

Look for hidden relationships

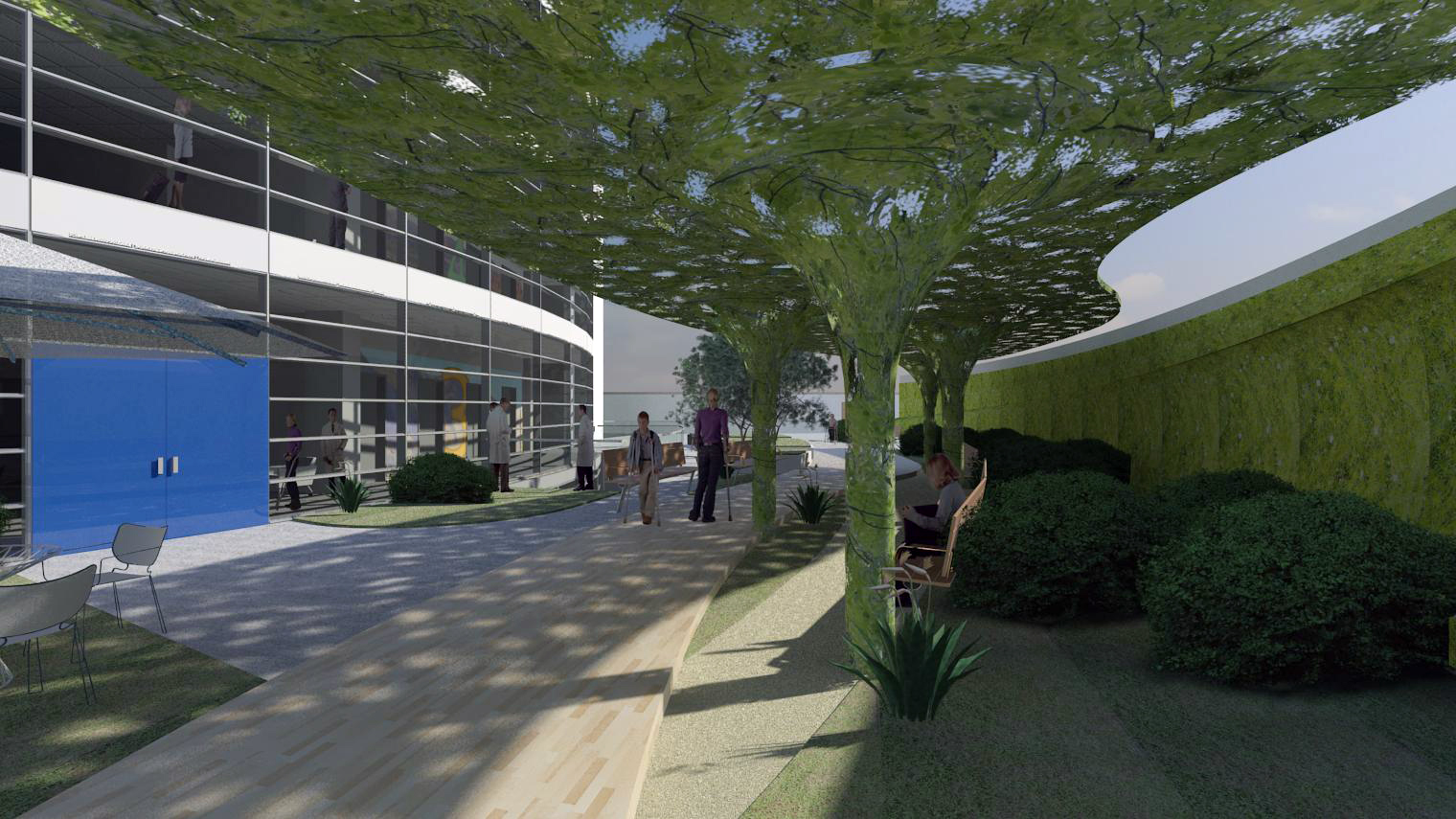

When advocating the triple bottom line approach, it is important to establish causal relationships between social and ecological benefits and financial outcomes. Daylighting strategies are a good example. Increased daylighting is associated with energy savings, but the bigger impact comes in the effect on patient care. Evidence-based design research has shown us that patients respond positively to increased daylight and views, demonstrate faster recovery times, and express more satisfaction with their care. Similarly, increased daylight and views have been associated with lower staff stress levels, reduced absenteeism and lower turnover. Though these implications might not reduce the up-front costs of adding more windows and daylight wells, they can have tremendous impact on overall cost, especially when you consider that construction costs represent only about 15 percent of a building’s lifetime cost. Staff actually represents the largest portion of a hospital’s operational costs, so initial investments in their happiness can bring big returns.

Even small decisions, such as choosing more expensive, no-wax sheet vinyl flooring over cheaper but more maintenance-intensive Vinyl Composite Tile (VCT), can educate clients on the value of balancing the triple bottom line, and facilitate the change in culture needed to truly usher in an era of sustainable design, where green space has as much value as built space and net-zero energy hospitals are not just the stuff of dreams.

This post was contributed by Michael Compton, LEED AP BD+C, while he served as a designer at Gresham Smith.