State and local transportation agencies face many challenges when trying to address their road safety and mobility needs. Availability of funding is a ubiquitous challenge for projects of all scales. Additional challenges often involve the physical constraints of trying to construct roadway improvements while minimizing the social and environmental impacts as well as affiliated costs such as utility relocations. The objective to “right-size” a roadway project is critical in the current circumstances transportation agencies operate in. Flexibility in applying road design criteria is an essential ingredient to achieving cost-effective designs and why agencies should consider performance-based design.

We recently sat down with Mark Doctor, principal design engineer in Gresham Smith’s Transportation market, to explore some changing perspectives regarding road design and the emergence of performance-based design approaches. With over 37 years of experience in transportation engineering, including 20 years in his previous role as a senior safety and design engineer with the Federal Highway Administration, Mark shares some valuable insights about the future of roadway design practices.

What is performance-based design, and how is it different?

Mark Doctor: Performance-based design emphasizes that conditions vary among different projects and that one-size-fits-all solutions can lead to inefficiency and higher costs. Performance-based design focuses on achieving a project’s purpose and need in ways that apply flexibility to selecting geometric design criteria (i.e. design speed, lane and shoulder widths, etc.) to allow agencies to implement cost-effective solutions to the specific challenges of the project.

Sometimes also referred to as practical design or performance-based practical design, the concept involves a fundamental shift in thinking about how agencies can achieve the best “return on investment” from projects. Using a performance-based approach to design decision making can help transportation agencies focus on scoping a project to meet the identified performance improvement needs without unnecessarily exceeding them.

Traditional road design practice relies heavily on following established geometric design criteria with a common perception that if the design of a project meets or exceeds the dimensional criteria, it will likely perform well. But good performance is not a “one-size-fits-all” proposition. Consider that many of the geometric dimensions used in roadway design today date back to policies and practices that are over 50 years old, which raises the question that perhaps a shift to a more flexible approach that considers ranges of design criteria could lead to the improved efficiencies needed today.

Although engineers have always considered various aspects of performance in road design, the currently evolving practices are attributable to a multitude of research conducted over the past two decades to improve our knowledge of the relationship between geometric design features and the degree of operational and safety benefits for road users. Using modern performance analysis methods and tools to inform design decisions is a key component of applying the approach.

What is prompting this change to a performance-based design approach?

Mark: I think a major factor is the hard reality that transportation agencies are having to deal with ever increasing needs to improve their road system and their available resources can’t keep pace. Also, the inevitable challenges of constructing projects within physically constrained conditions have led to a greater sense of urgency to seek more efficient and cost-effective design solutions.

Oftentimes design decisions are made with a focus on trying to maximize the benefit of a single project. This can result in “scope creep” and added cost. By shifting focus to meeting the project needs, goals and budget, agencies can strive to apply their resources in ways that maximize benefits across the broader system.

Another factor driving this change is the types of projects transportation agencies design today are different than they were when most geometric design criteria were originally developed. In the past, geometric design criteria were developed primarily for application on constructing new roads. Today, most projects involve improving existing facilities.

At its core, performance-based design is about “designing up” from the existing condition, to meet the stated needs and goals through customized and innovative solutions specific to the project.

What is a good example of how performance-based design could be applied?

Mark: One example that perhaps some people don’t think about is designing for a logical and practical level of operational performance. The desired level of operational performance influences some very consequential design decisions such as how many lanes are needed at an intersection for the various movements. Most agencies have guidelines for selecting operational performance levels based on the type of road facility and location context of the project. However, agencies should think flexibly when selecting operational performance goals.

For example, does it make sense to design an intersection along a corridor to a much higher level of operational performance in comparison to the adjacent intersections that are not within the project? Perhaps selecting an operational performance goal of improving that intersection to match those of adjacent intersections along the corridor is a more practical and cost-effective decision.

Designing for operational performance typically involves accommodating future peak-hour design volumes. Travel demand modeling is commonly used to forecast future traffic demands that inform selecting design volumes. Travel demand modeling is not an exact science and actual future traffic volumes may differ significantly from the model predictions. This can result in oversizing a facility if future traffic demands do not reach the modeled levels forecasted. Also, typical practice establishes design volumes based on peak conditions. If peak-hour congestion occurs at most other intersections along the corridor, is it a wise decision to invest additional resources into achieving a higher level of performance at just one intersection? Because operational performance has such a significant influence on key project design choices, agencies should consider the appropriate performance levels with flexibility in mind.

How can transportation agencies advance their safety goals by using performance-based design approaches?

Mark: Of all the performance aspects associated with road design choices, safety is perhaps the most critical but also the most challenging. A very important shift in thinking is how we measure safety performance. Historically, safety was measured in terms of the number of crashes. More recently, agencies have started to focus on establishing their safety goals based on the number of fatalities and serious injuries. This difference is a subtle but critical distinction.

The pivot to thinking about safety in terms of fatalities and serious injuries rather than crashes was part of the emergence of adopting a Safe System approach for addressing road safety challenges. One of the foundational principles to a Safe System approach is that people will make mistakes. Even the best of drivers, safest of pedestrians, or most skilled of bicyclists will at some time inevitably make a mistake. People will never be perfect. On the roads, making these inevitable mistakes can sometimes result in a crash.

A paradigm shift when adopting a Safe System approach is to acknowledge that crashes will occur on our roads. We can’t eliminate crashes. However, we can mitigate the consequences of crashes so that when they occur, they don’t result in death or serious injury. Understanding this distinction is critical to understanding the Safe System approach. This principle is sometimes compared to the “harm reduction” concept used in public health sectors.

By shifting the focus of safe design to one that reduces deaths and serious injuries, designing to achieve appropriate vehicle speeds then becomes a critical performance metric for safety. Designing for a “target speed” on a project is an example of how agencies are evolving toward performance-based design. Target speed is typically defined as the highest speed at which vehicles should operate on a road, consistent with the level of multi-modal activity generated by adjacent land uses.

Applying the target speed concept in design decision making is different from traditional use of design speed on a project. A design speed is a selected speed that determines certain geometric design features. However, strategies beyond geometric design may be needed to achieve operations at the target speed.

On roads where higher vehicular speeds are appropriate based on the context and classification, providing physical separation of vulnerable road users from motor vehicles can allow for higher speeds. Designing for safety means designing road features so that when a crash occurs the forces of the collision that are transferred to the human body are kept at survivable levels.

What are some of the key challenges for applying performance-based design?

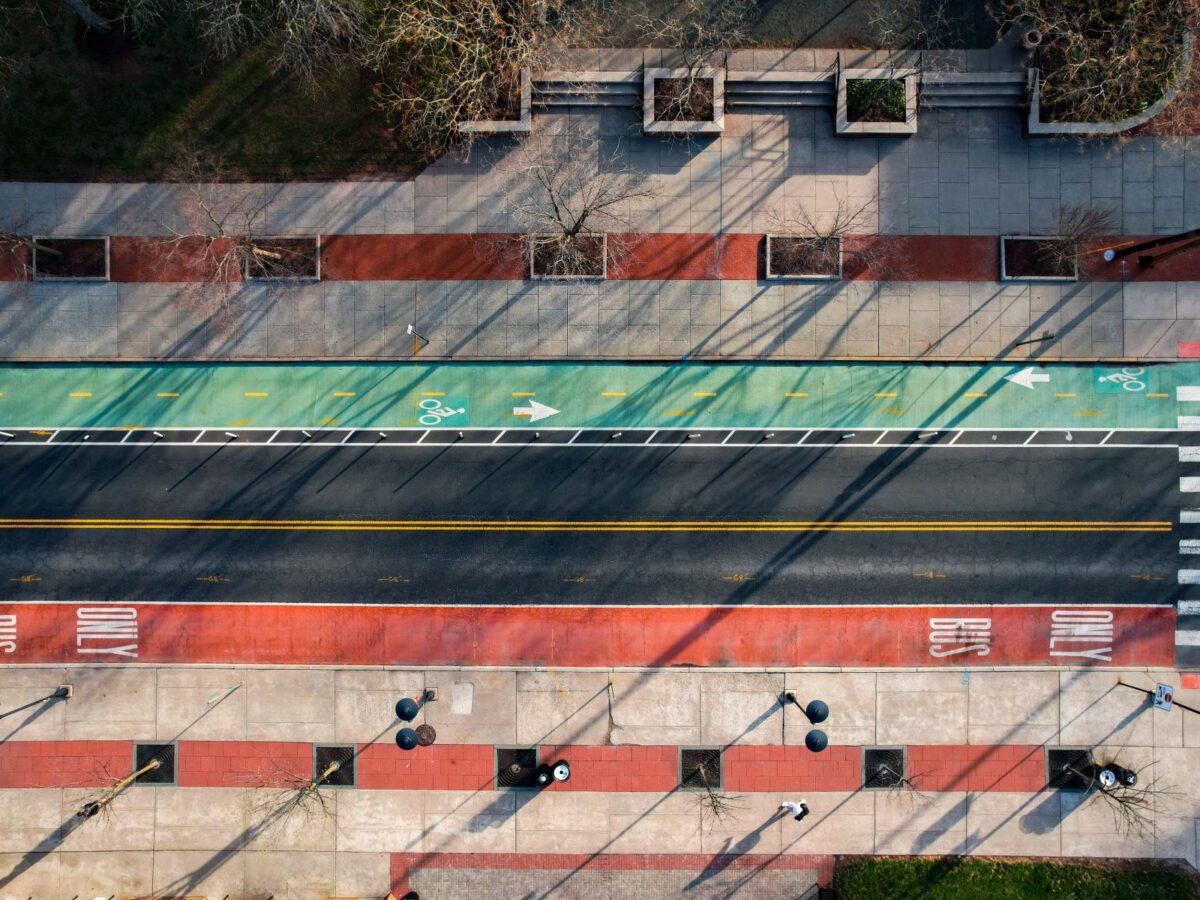

Mark: Performance should be assessed for all users of the facility. Too often only motor vehicle factors are considered. Performance-based design should also include designing to meet the goals and objectives for pedestrians, bicyclists, public transit users, and freight vehicles.

Another challenge is that not all aspects of performance related to design are known. There is still so much we don’t know and may never know. Also, some performance aspects are not readily quantifiable, and practitioners will need to apply a blend of both quantitative and qualitative assessment methods and tools to consider performance. Most engineers like the simplicity of using a singular assessment method or tool since that helps reduce potential inconsistency. However, since no current method or tool covers all aspects of performance, we need to blend what methods are available.

An analogy I like to use is a jig-saw puzzle with multiple pieces missing. Although it may be frustrating that we don’t have a completely solved puzzle, by putting together the pieces we do have we can at least identify what image is depicted on the puzzle. Sometimes having the “big picture” is sufficient to make smart decisions even if a few details are missing.

With transportation agencies across the country facing budgetary constraints, performance-based design offers a flexible approach for agencies to meet their key performance goals by developing practical and cost-effective solutions.