According to Becker’s Hospital Review, the United States may face a shortage of almost 5.7 million nurses by 2030. A physically demanding, mentally challenging and emotionally exhausting profession, nursing is characterized by historically high turnover rates and staff shortages, adversely affecting patient care and operational efficiency.

The intensive care unit (ICU) is one of the most stressful environments for nurses, who deal with patient morbidity, mortality, traumatic events, including violence, and the need to support distressed and grieving families. Nearly 50% of ICU nurses experience burnout syndrome, a problem exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, leading many seasoned professionals to retire early or leave the profession altogether. Despite evidence that environmental design can help reduce work-related stress, an adequate tool to identify physical environmental stressors for stress moderation has been lacking.

Dagmar Rittenbacher, a Healthcare design researcher at Gresham Smith, has addressed this gap as lead author of a Health Environments Research & Design Journal publication titled: “Preliminary Development of Items for a Nurses’ Physical Environment Stress Scale.” Co-authored by Lesa Lorusso, Gresham Smith’s Healthcare director of Research and Insights, along with Sheila J. Bosch and Shabboo Valipoor, both associate professors at the University of Florida, the research focuses on creating a tool to assess how the physical environment can moderate stress levels among ICU nurses. We recently spoke with Dagmar and Lesa to learn more about their work.

Tell us about the development of the preliminary Nurses’ Physical Environmental Stress Scale (NPESS) tool and why you felt it was important.

Dagmar Rittenbacher: The impetus behind developing this tool stemmed from the alarming number of ICU nurses leaving the profession due to the COVID-19 pandemic. And it’s a trend that continues to grow. The genesis of this project traces back to our ongoing research work with Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare as part of its ICU redesign at M.T. Mustian Center.

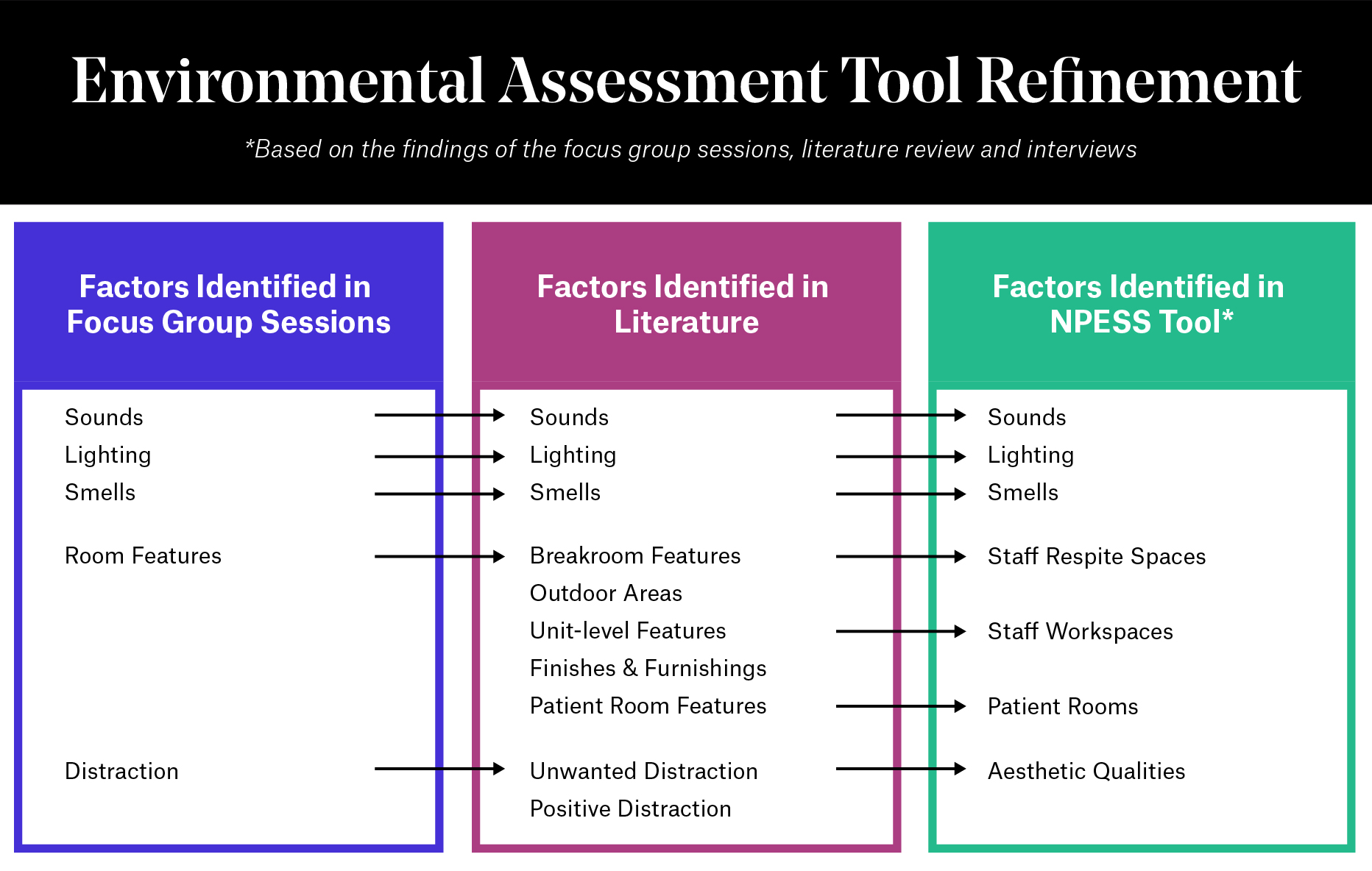

The initial steps in developing the NPESS tool involved analyzing data from focus group sessions with ICU nurses at TMH. We then explored existing research tools used to evaluate environmental factors in healthcare settings. While some tools proved relevant, none specifically addressed nurses’ physical surroundings. Leveraging data collected from Gresham Smith’s study at Tallahassee Memorial Hospital, coupled with an analysis of relevant literature, played a pivotal role in the tool’s development.

Lesa Lorusso: Our post-occupancy evaluation for Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare, which Dagmar mentioned, focused on acoustics and the built environment’s impact on patients and staff. This evaluation provided significant insights into the differences between the old and new ICU spaces at Tallahassee Memorial. The new design, which we call “on-stage/off-stage,” emphasized creating a curated sensory experience, which is crucial from an architectural perspective.

During the evaluation, we employed “Design Thinking” to conduct workshops with ICU nursing staff. The initial focus group workshop was held in the old ICU space at Tallahassee Memorial Hospital before construction began on the new one. We engaged ICU nurses in a series of activities to better understand their sensory experiences in the ICU from an empathetic standpoint.

The second focus group workshop, held post-renovation in the new space at the M.T. Mustian Center, measured changes and improvements. This Design Thinking approach placed ICU nurses at the center of the problem-solving process, highlighting their pain points, and guiding us on what worked well and what needed improvement.

By the end of the study, we had a wealth of data but no specific tool to measure how the built environment affects nurses’ stress levels. Dagmar recognized the potential impact of focusing on this issue. I provided her with all our collected data and said, “Just take this and run with it!” And she did exactly that, using the information as a foundation to develop the NPESS tool, which holds incredible promise.

“It’s not surprising the ICU has been likened to a “war zone.” The sensory overload from constant sounds, odors and other stimuli is overwhelming…”

What are some of the primary contributors to physical environmental stress for ICU nurses?

Dagmar: ICU nurses face significant stress from various sources. Extended shifts, exposure to infectious diseases like COVID-19, poor nurse station design and unit configuration, long distances to walk during shifts, unpleasant smells, and inadequate natural light all contribute to heightened stress levels. Noise levels in ICUs can also be exceedingly high due to monitor alarms and machine noises, which nurses find both stressful and distracting.

For perspective, the average noise level in an ICU reaches 71.9 decibels, far exceeding the World Health Organization’s recommended levels of 35 decibels during the day and 30 decibels at night. It’s not surprising that the ICU is often likened to a “war zone.” The sensory overload from constant sounds, odors, and other stimuli is overwhelming and has been linked to emotional exhaustion, PTSD, burnout, and compassion fatigue among ICU nurses. Additionally, both patients and staff can suffer from ICU-related psychosis as a result.

How does the NPESS tool measure physical environmental stress?

Dagmar: The NPESS tool is a questionnaire with 81 items derived from analyzing the focus group data as well as relevant literature. These items address factors identified as potential moderators of stress in ICU settings. The questionnaire is divided into seven sections: sounds, lighting, smells, staff respite spaces, staff workspaces, patient rooms and aesthetic qualities.

Each question evaluates environmental factors that could potentially influence stress levels among ICU nurses using a 5-point Likert-type scale, where 1 means “never” and 5 means “not applicable.” There is also an option for an “ambiguous question,” allowing nurses to highlight items they find unclear or poorly worded. To refine the tool, we distributed the questionnaire to a group of 10 ICU nurses to gather their feedback on the items, wording, length and question flow. Based on their input, we made the necessary modifications.

“One of the greatest benefits of the NPESS tool is its capacity to adapt to the continuous changes in the healthcare landscape.”

What are some of the implications for practice?

Dagmar: Our findings indicate that the tool can assist in the design of new ICUs or the renovation of existing ones by serving as a checklist of physical environmental factors or features that should be incorporated to reduce stress among ICU nurses. These features include well-designed ICU units that streamline the operating process and reduce walking distances for nurses, windows with views of nature, and the use of cutting-edge finishes such as acoustical ceiling tiles, softer flooring and noise-absorbing materials to minimize noise levels.

Lesa: I think it’s important to note that this project represents a major team effort, extending beyond our Research and Insights group to the design team in our Jacksonville office. Skip Yauger, a senior vice president of Healthcare at Gresham Smith, supported our R&I group in conducting research at Tallahassee Memorial Healthcare’s ICU spaces due to his strong belief in the role of research and design. The focus on acoustics and sensory stress initially came from Skip’s research efforts in collaboration with Brian Schulz, a senior Healthcare architect in our Jacksonville office. This project is a great reminder that research thrives on the strong collaboration between architects, designers, clients, practitioners, and research groups like ours.

Dagmar: Building on Lesa’s point, this project beautifully illustrates the ripple effect of collaboration and how different perspectives, skill sets, and disciplines can come together to tackle some of the most complex challenges in healthcare design, such as reducing physical environmental stressors for ICU nurses. One of the greatest benefits of the NPESS tool is its capacity to adapt to the continuous changes in the healthcare landscape. I’m excited about its potential to not only enhance operational efficiency and empathy, but also to enable architects and designers to accommodate these ever-evolving needs in future designs.